Paralysed by growth: A lake under siege

Wednesday, 11 April 2018

Fish farms on Laguna de Bay (Nick Greenfield/UN Environment)

“When I was a boy, the lake was beautiful,” Bernardo San Juan says. “In the early 70s we would picnic here and swim in the lake. We would just bring a pot and some rice, we would catch fish to cook and drink the lake water. Today, it’s a different story…”

Today, in fact, the lake is hardly visible. Instead, vast swathes of the water around the lakeside Filipino town of Cardarno are a sea of green, fish pens and navigation channels alike clogged by an impenetrable mass of water hyacinth.

“You can see we are paralysed right now,” Bernardo, Cardano’s mayor says. “We are a fishing town – can you imagine the effect of that on our daily lives? Almost all the population are in the fishing industry – we don’t have any factories here. That is the source of our living.”

With the town’s fishing port blocked and navigation at a standstill, a ‘State of Calamity’ has been declared in Cardona. While authorities work to clear the weeds choking the town, its fishing fleet stands idle and transport to and from the island of Talim, home to half Cardona’s 50,000 people, has ground to a halt.

“Right now they are isolated – they are totally isolated. Because the only way to get to them is by boat. It’s stopped more than 90 per cent of the transport to and from the island. The little boats just can’t get through.”

“It’s a perennial problem,” Mayor Bernardo says ruefully. “A perennial problem we could have controlled.”

Hemmed in: Fed by nutrient waste, a super bloom of water hyacinth has paralysed the lakeside town of Cardano. (Nick Greenfield/UN Environment)

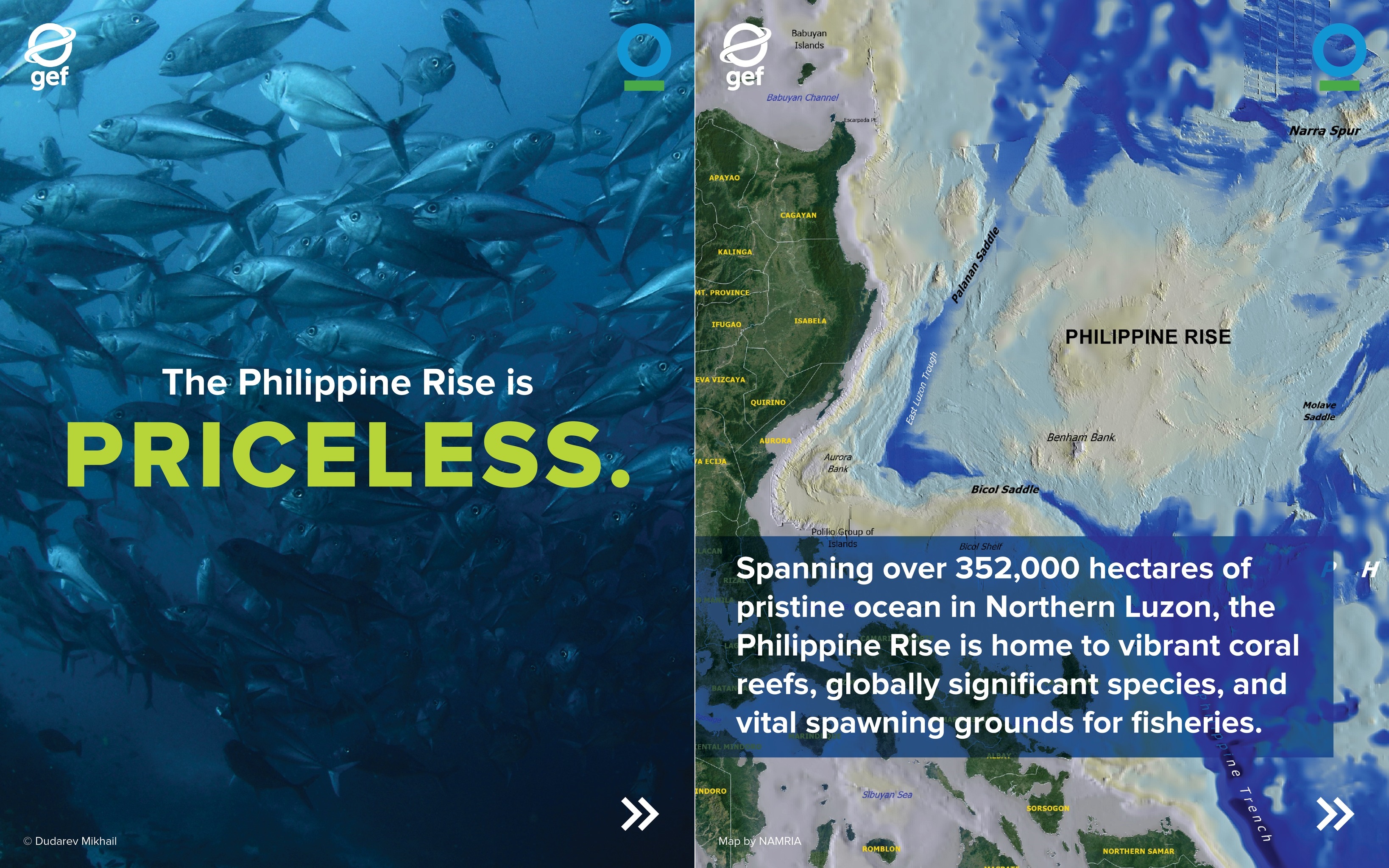

Laguna de Bay is the Philippines' largest lake. At over 900 hectares in size and bordering the rising mega-city that is Metro Manila, it is one of the aquatic "three sisters" – Manila Bay, the Pasig River and Laguna de Bay – around which the Filipino capital was founded over 400 years ago. With its fishing and aquaculture industries supplying more than 40 per cent of the capital’s fish, and its waters becoming ever more important for both agriculture, industry and domestic supply, Laguna de Bay is one of the Philippines most vital natural assets. But as the region’s population grows, the lake is also at risk.

The problem is nutrients – primarily nitrogen and phosphorus compounds – that come from fertilizer runoff, livestock runoff and wastewater. While to many of us nutrients sound like a good thing (who doesn’t need a more nutritious diet after all?) – in the case of our rivers, lakes and oceans, an excess of nutrients from human activity is amongst the deadliest threats of all.

This is the global "nutrient challenge" – the delicate balancing act between feeding and providing for growing global population and upsetting the natural balance that allows our ecosystems to function.

When excess fertilisers and other by-products of production and consumption (not least human waste) enter water bodies, they bring with them an increase in nutrients (a process known as eutrophication) that encourages the growth of huge blooms of algae, water hyancinth and other nitrogen and phosphate-loving species – fast upsetting the balance these aquatic ecosystems have developed over thousands of years. Algae in particular not only block sunlight, preventing the survival of other species, but release potent neurotoxins – such as microcystins (blue-green algae), which destroy nerve tissue in mammals or domoic acid (‘red tide’ algal blooms), which accumulates in shellfish and other species causing injury or even death in higher-level predators from birds to sea mammals to people.

When the algae die, their decomposition leaches the surrounding water of oxygen, causing aquatic hypoxia – a shortage of oxygen that causes mass fish die offs – and eventually aquatic dead zones, barren stretches of water where neither fish nor plants are able to survive. And these dead zones are on the rise. In 1960, there were an estimated 10 oceanic dead zones worldwide. By 2008 this figure had risen to 405 – some as large as 70,000 square kilometres. Today, there are more than 500.

According to UN Environment’s Christopher Cox, the global nutrient challenge is one of the key environmental issues facing the planet today.

“Building awareness of the nutrient challenge is crucial,” Cox says.

“Nutrient loads into coastal areas rose as much as 80 per cent between 1970 and 2000, but more than 80 per cent of wastewater is still released into the environment without treatment. If we don’t address this issue, the results – from ocean hypoxia to toxic algal blooms – could be catastrophic.”

“We are a fishing town – can you imagine the effect of that on our daily lives?” : Mayor of Cardano, Bernardo San Juan. (Nick Greenfield/UN Environment)

“It is a wicked problem – not just because we are so reliant on synthetic fertilisers to feed a growing population, but because nutrient pollution is largely invisible until it’s too late.”

Cox leads the Global Environment Facility-backed Global Nutrient Cycle project– a $4 million initiative working to kickstart international efforts to address the nutrient challenge. Alongside undertaking research on nutrient loading and developing tools to predict and counteract the impacts of eutrophication, the project is working with partners in the Philippines to pilot these approaches – providing vital support to the efforts to save Laguna de Bay and its sister waters.

One output of the project’s efforts has been a series of ecosystem health "report cards" produced with partners PEMSEA and the Laguna de Bay Lake Development Authority, providing a snapshot of the state of the lake in terms of both water quality and fisheries.

The results? Not the kind of grades you would want to take home to mother. Laguna de Bay scored a low C- in water quality, with heavy phosphate and coliform loading, and a failing F for the state of its fisheries, with major problems in terms of invasive species, overfishing and declining natural food sources.

While agricultural and industrial runoff both have a role to play in the lake’s declining health, the biggest contributor to eutrophication – and thus the water hyacinth bloom paralysing Cardona – is human waste. Specifically the domestic waste and untreated sewage that flows into the lake daily from the more than 12 million inhabitants of the 29 towns and hundreds of informal settlements that ring its shores.

“Eighty per cent of the biochemical oxygen demand [an indicator of organic pollution] is from household pollution,” Laguna de Bay Lake Development Authority General Manager Jaime ‘Joey’ Medina says.

“The number of households without proper toilet facilities is still very high. That’s one of the biggest problems. Thousands of houses directly discharge into the lake. And it's increasing tremendously.”

Growing migration as households are displaced from Metro Manila and elsewhere for infrastructure projects is fast straining the ability of the environment around Laguna de Bay to cope.

Watery wastes: Stripped of oxygen, oceanic dead zones are on the rise around the globe. (NASA / Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen)

“There might be 100,000 informal settler families in just one town. And with five to six people per household, that just shows you the magnitude of the problem,” Medina says.

“Sewerage systems are the responsibility of the water utilities here in the Philippines. And according to their commitment to the government, they can provide full coverage by the year 2037. So the problem is from now up to 2037. We cannot wait for that period of time, something must be done now. That’s the challenge – how can the government control the increasing pollution brought about by a massive increase in population.”

And while the water hyacinth bloom paralysing Cardona might be the most obvious effect of Laguna de Bay’s pollution problem, other, less visible impacts are having an effect well beyond its shores – reaching as far as the food and water needs of the capital itself.

Fish in the lake, both free and farmed, rely on naturally occurring phytoplankton as their primary food source. With increasing eutrophication and decreasing oxygen levels in the lake, these species are also taking a hit – and no plankton means no fish.

“In the 70s, fish could grow for three to four months and then they could be harvested,” Mayor Bernardo says. “Right now, sometime its takes more than a year and you cannot even harvest them. That’s the situation right now.”

The bay is also seen as an increasingly valuable source of water for the growing metropolis – with plans for it to supply as much of 15 per cent of the capital’s needs in the future. But the cost of treating that water is a stumbling block, with each litre drawn from Laguna de Bay costing some 25 cents to purify, more than quadruple the treatment costs of water from the region’s major dams.

It is, according to Christopher Cox, a prime example of the growing challenge of balancing the needs of growing urban populations with the survival of the ecosystems that they live within and alongside.

“With Manila’s population growing at close to 1.5 per cent annually, managing the food, water and energy needs of those people means both conserving and harnessing the potential of Laguna de Bay and Manila Bay. It’s a delicate balancing act – and one that government, business and citizens will have to work together to achieve.”

But while the challenges may be significant, so is the will to overcome them. With the help of the Global Nutrient Cycle project, UN Environment and partners are supporting the work of the Global Partnership on Nutrient Management – a coalition of governments, scientists, policy makers, businesses, NGOs and international organisations working to build awareness of the nutrient challenge and develop urgently needed solutions.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, backed by the data made available through the ecosystem health report cards and building on the momentum of the nation’s landmark 2008 supreme court decision compelling urgent action to rehabilitate Manila Bay and its sister waterways, the Laguna de Bay Lake Development Authority is working with partners across government, the private sector and civil society to secure the lake’s future.

Population boom: Informal settlements line many of Manila’s waterways. (Nick Greenfield/UN Environment)

One such initiative is CLEAR, a partnership between the Lake Development Authority, the Society for the Conservation of Philippine Wetlands and Unilever that is banking on youth as the key to environmental sustainability. CLEAR hosts regular "eco-camps" for high-school students, educating them on environmental issues and funding student-led projects to improve the environment in their communities.

“When it comes to the older generation – they’re so close-minded. There is little chance of changing their mindset,” Medina says. “So the opportunity now is with these high-school students … and hopefully, what they learn from eco-camps like that they bring to their schools, they bring to their families, they bring to their communities – and slowly, I think we could make a difference.”

Former Unilever Philippines Vice President Chito Macapagal, one of the instigators of the eco-camps, sees collaboration between the private sector, public agencies and civil society to improve the Philippines’ waterways as more than corporate social responsibility, but as plain good business.

“We’re all in the business of water,” Macapagal says. “You need clean water to cook your food, you need clean water to drink your tea, you need clean water to take a bath and shampoo your hair, and we need clean water for our factory… so what other business case do you need? In the end it’s a very pragmatic approach. People talk about creating shared value – and this is a textbook case, because there is an intersection of what the business needs and what you can help the society with.”

“Together, we want to make sure that people understand the importance of Laguna de Bay to the life of people within the area, but also to show that they can actually help – that there are things that they can do. So it’s not just talk – it’s giving them tools for them to be able to do something.”

The challenges facing Laguna de Bay might be complex, but by working across sectors and agencies to address issues, from environmental awareness, to waste management to sustainable fisheries, Jamie Medina believes a clean future is within reach.

“My family came from this island,” Medina says, indicating his hometown on a map of the lake. “My vision is to see the lake clean, with the people around the lake getting the benefits – not the big industries, the big corporations, but the small fisherfolks. A multi-sectoral and multi-agency approach is needed, but together, we can do it.”

The Global Nutrient Cycle project and the Global Partnership on Nutrient Management are supported under the Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities (GPA) – a global inter-governmental commitment to address the accelerating degradation of the world’s oceans and coastal areas by encouraging governments and regional organizations to prepare and implement comprehensive, continuing and adaptive action plans to protect the marine environment. The GPA is hosted by UN Environment.

Further coverage on battling pollution in the Philippines' largest lake.

Originally published by United Nations Environment