Recalibration and revitalization: Sorting out Cavite’s trash

Thursday, 23 February 2023

This is an early release of reporting PEMSEA and our partners have produced from the Ecological Solid Waste Management in Cavite Province Project, a full project report is expected soon!

How data analytics took a solid waste management project, funded by Coca-Cola Foundation Philippines, Inc. and implemented by PEMSEA, to a whole new level

WHAT happens when a solid waste management (SWM) program set for implementation in a province with a big garbage problem and no landfill of its own, is derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic? It gets back on track by undergoing a recalibration that employs robust data analytics to determine exactly what people need, resulting in appropriate plans and actions that have produced model communities, even in the most challenging situations.

The Ecological Solid Waste Management (ESWM) in Cavite Province (Plastic Wastes Recycling Project) was funded with a grant from the Coca-Cola Foundation Philippines Inc., and implemented by the Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA) in partnership with the Caritas Diocese of Imus Foundation, Inc and in close coordination with Cavite’s Provincial Government Environment and Natural Resources Office (PGENRO).

Originally set for January 2020 to June 2021, with an extension until December 2021, the project’s main objective was to support the diversion of solid waste generation in the province, where the 10-year Provincial Solid Waste Management Plan had set a target of reusing, recycling, composting, and recovering at least 30 percent of its waste. Other goals were to enhance the awareness of people to implement SWM programs and promote a circular economy; to ensure the SWM program’s sustainability beyond the project’s lifespan, and to replicate it in other Cavite communities; and to share lessons and best practices not only within Cavite, but with other local government units (LGUs) in the PEMSEA Network of Local Governments (PNLG).

Five project sites had been identified in Cavite: Brgy. San Rafael 3, Noveleta; Brgy. B. Pulido, General Mariano Alvarez (GMA); Brgy. San Jose, Tagaytay City; Brgy. Bucana, Ternate; and Brgy. Banaybanay, Amadeo. Also partnering with the project was the Caritas Diocese of Imus Foundation, Inc., specifically its Apostolado sa Larangan ng Pagtataguyod sa Buhay (Social Action Commission), whose Sustaining Empowered and Resilient Communities through Holistic Development (SEARCHDEV) Program originally reached out to Cavite’s indigent areas with training in community-based disaster risk reduction (DRR), rescue, and emergency response. It was Caritas, social action arm of the Archdiocese of Imus, which identified some of the most vulnerable communities as project sites.

Garbage everywhere

“We did community profiling, and lumabas sa lahat yung problema sa basura (the problem of garbage came up everywhere),” says Jerel Tabong, program manager and team leader of lay pastoral workers in Caritas Imus. Initially, the reason was obvious, Tabong notes: trash clogged waterways and caused flooding. “But later on, through formation, education, training, and awareness sessions on the environment, they realized hindi nahihiwalay sa pananampalataya (it can’t be separated from their faith) to become good stewards of the environment.”

Tabong also points out the organization’s three-point mission of KKK—”kapwa, kalikasan, at kita” (other people, nature, and livelihood)—and how these must always be part of the equation. He illustrates the garbagegenerating social divide even in the purchase of shampoo: “While the rich can buy big bottles, the poor can only afford plastic sachets—and those can accumulate.”

The project also worked with the Provincial Government of Cavite through the Provincial GovernmentEnvironment and Natural Resources Office (PGENRO). “Republic Act 9003 (the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000) started in 2000, so we appointed our ENROs and established our SWM division after that,” recounts Cavite PGENR Officer Anabelle Cayabyab. “Our first provincial SWM Plan ended in 2018, and we hope to get the new version approved by 2023. “Marami na rin nagbago, pero marami pa rin plastic” (A lot has changed, but there’s still a lot of plastic). Compliance is difficult even at the barangay level; they can segregate, they can follow the protocols in terms of how to manage trash, but at the end of the day, we still throw our trash in another province’s landfill.” As specified in the new plan, the province of Cavite should have its own landfill by 2023, with Maragondon as the potential site, Cayabyab says.

The original project’s components were plastic waste recycling, including constructing a plastic recycling facility; capacity building; information, education, and communication (IEC) and knowledge sharing; and livelihood development. Four awareness and training sessions were completed during the original project period, with 155 attendees from the five communities. There were community engagement and empowerment sessions in five barangays, and clean-up drives in Brgy. Banaybanay.

“Bakit mahalaga ang tamang plastic waste management? (Why is proper plastic waste management important?)” reads some educational material produced for the campaign. The answer: “Nagiging sanhi ng polusyon sa kalupaan, karagatan, nakakasama sa kalusugan, at maaring magdulot ng sakuna kagaya ng matinding pagbaha.” (It becomes the cause of land and sea pollution, it’s bad for the health, and it can cause disasters like intense flooding.)

A tsunami warning sign in Bucana, Ternate is proof that the coastal community remains vulnerable to storm surges, flooding and other natural disasters which are aggravated by issues of improper waste management.

A tsunami warning sign in Bucana, Ternate is proof that the coastal community remains vulnerable to storm surges, flooding and other natural disasters which are aggravated by issues of improper waste management.

Income-generating work

In livelihood development, 110 individuals, mostly women, were given additional income-generating work, such as crafts (doormats, rags, plastic and paper decorative flowers, and other handicrafts) in San Jose, alamang (tiny shrimp made into fish paste) and patis (fish sauce) processing in Bucana, and sewing in B. Pulido. Cavite’s Department of Science and Technology, the Department of Trade and Industry, and the Provincial Cooperative, Livelihood & Entrepreneurial Development Office (PCLEDO) in Cavite provided further livelihood enhancement support through product assessment and labeling, participation in local market bazaars for product marketing, and involvement in DTI’s One Town One Product (OTOP) program.

Women earn extra income from a rag-making livelihood program in B. Pulido, GMA. (Top) Norlita Perez of Bucana, Ternate shows off the ‘alamang’ that is the raw material of the community’s livelihood program. (Bottom)

Women earn extra income from a rag-making livelihood program in B. Pulido, GMA. (Top) Norlita Perez of Bucana, Ternate shows off the ‘alamang’ that is the raw material of the community’s livelihood program. (Bottom)

A plastic recycling facility was also set to rise in Banaybanay. However, the community-run facility never opened due to several factors: First, the community wanted a clear environmental and social impact assessment due to concerns over potential air and water pollution from the operation of the plastic recycling machine. Second, PEMSEA, Caritas, and the PGENRO were concerned about the available supply of plastics, given the lack of initial assessment and quantification of the volume of plastics and residuals from the identified barangays. Third, the manufacturer failed to deliver the equipment due to impacts of the global pandemic on its production schedule. Thus, a proposal for a recalibration and adjustment of the ESWM project, which also requested that the project be extended until December 2022, was submitted and approved by the Coca-Cola Foundation Philippines Inc. on December 17, 2021. All plans relevant to the adoption and implementation of a solid waste technology were put on hold until data analytics were carried out, in the form of a plastic circularity audit, a community needs assessment (CNA), and a waste analysis and characterization study (WACS).

Survey of junkshops as part of the plastic circularity audit.

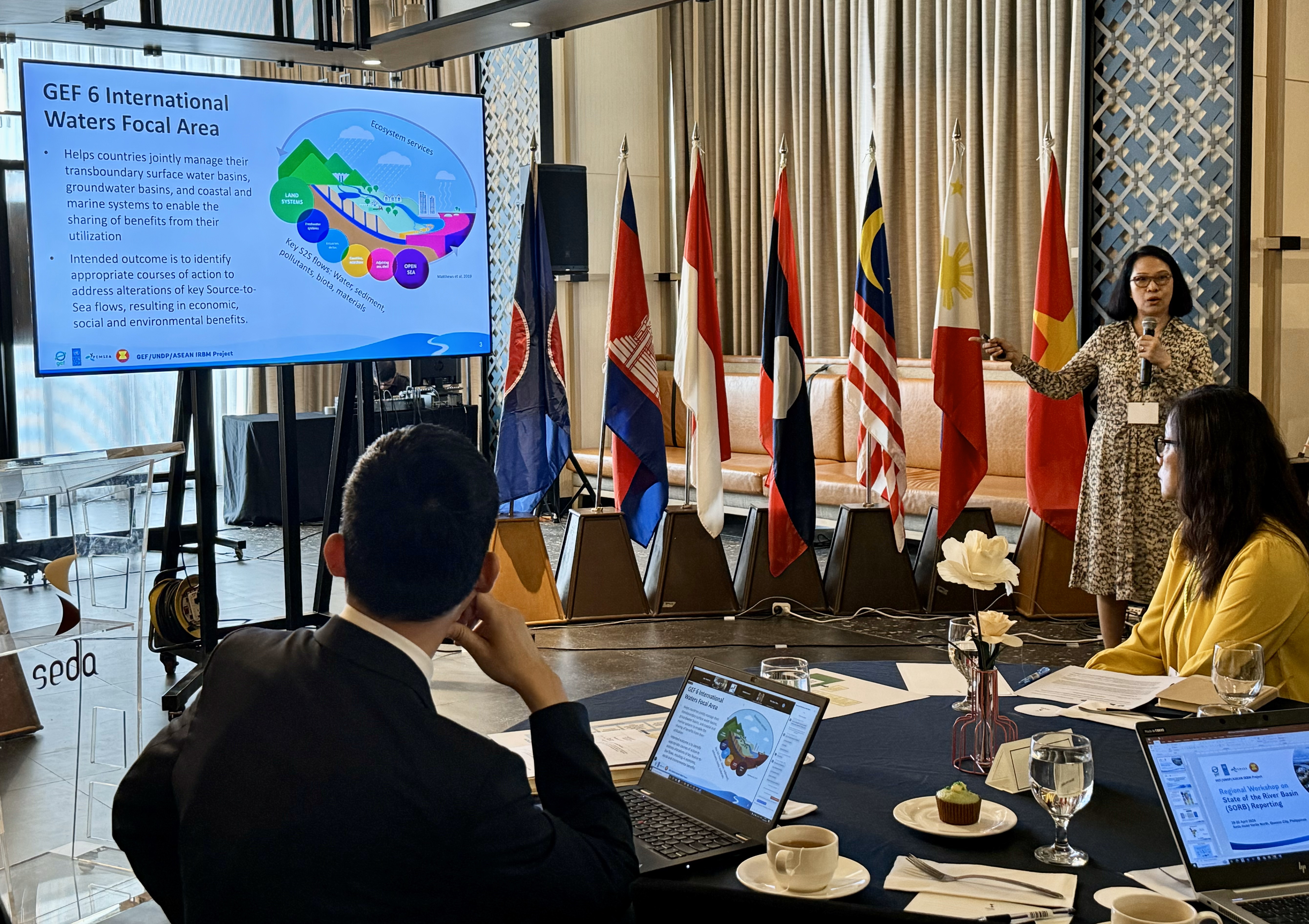

The plastic circularity audit of the five LGUs was accomplished in November 2021, and listed junkshops, types of waste handled, and aggregators and recyclers for plastic, paper/carton, and other kinds of trash. The CNAs in the five barangays were held in December 2021, with an average of about 30 participants, most of them female. Community members still recall the thought-provoking consultations, which were divided into three sessions: “Basura Ko, Kilala Ko” (I Know My Trash)–Identification and Classification of Wastes; “Basura Ko, Obligasyon Ko” (My Trash is My Obligation)–Identification of Best Practices and Actors; and “Basura Kayang Pamahalaan, Kayang Gampanan” (Trash Can Be Managed, Acted On)–Identification of Gaps, Action Plan, and Actors. Biodegradables and recyclables were the dominant waste types based on the CNA, and the communities’ limited understanding of the types or classifications of wastes was observed, which may impact the implementation of proper waste segregation.

Identifying the gaps, challenges and actions for improving solid waste management that are practical, doable and community-owned through the community needs assessment.

Participants got some much-needed awareness raising on how to implement RA 9003 in the local communities, and the four main categories of waste—Biodegradable, Recyclable, Residual, and Special. “Pinakamahirap yung (The hardest part is) awareness,” recalls San Jose barangay captain Norelyn Parra. “Hindi nila alam kung ano yung RA 9003! Alam nilang tungkol sa basura, pero pagkatapos noon, wala na. Kailangan dalhin mo ang kaalaman sa kanila.” (They don’t know what RA 9003 is! They know it’s about garbage, but after that, they know nothing. You have to bring the awareness to them.) The analytics revealed a much clearer SWM profile of the five LGUs in Cavite. The information included frequency of trash collection, how many MRFs there are, how many junkshops the LGU is working with, which landfill the trash goes to (mainly in Rizal and Laguna), any SWM machines like composters in the barangay, and any ordinances which the barangay has carried out in support of SWM.

The WACS, meanwhile, was tantamount to peering into the trash cans of barangay residents. Results revealed that biodegradables accounted for 39–50 percent of garbage in all five target Cavite LGUs.

Mostly biodegradables

In the five project site barangays, biodegradables made up 15–64 percent of the trash, which could be composted and used as natural fertilizer for urban and community gardening, and in the production of charcoal briquettes (such as in San Jose, Tagaytay). Recyclables accounted for 12–63 percent of total volume; these can be sent to an existing material recovery facility (MRF) or material recovery system of the barangay, or to the plastic CARE spaces (for Community Action to Restore the Earth) that will be created to improve the sorting, collection, and storage of recyclables which can be sold to junk shops for added income. Residuals with potential for recycling accounted for 6–14 percent of garbage, and could potentially be processed into sachet ecobags as a livelihood option. Residuals for disposal made up 5–26 percent of garbage volume, and special waste rounded out the analysis at 1–4 percent.

Many valuable lessons were learned from the studies, among them the need to strictly enforce a “no segregation, no collection” policy in barangays, the impetus for backyard composting of the huge amount of biodegradables, the constant need for awareness generation, and, most recently, the need for better guidelines on what to do with hazardous waste in the light of the pandemic. “In the development of our COVID management plan for hazardous waste, we called all LGU sanitary engineers and municipal ENROs, and learned that special waste like personal protective equipment (PPE) and masks are not properly managed, but are included in regular wastes,” notes PGENRO Cayabyab. “Others make the barangay’s MRF or MRS the storage area, which is not correct. We have to address the readiness of an LGU to handle hazardous waste.”

As it comes to a close, however, the benefits and impact of the ESWM Project have become clear. First, the province, municipal and barangay LGUs, and Caritas now have updated data that can help inform further actions to manage solid and plastic wastes more effectively. The circulatory audit has helped the province of Cavite strengthen the database for junkshops, monitor their compliance, and develop potential linkages between the communities and the junkshop operators for the handling of recyclable wastes. The CNA pinpointed more accurately the good practices, including gaps and needs in the communities, on solid waste management, as well as identified actions for strengthening solid and plastic waste management that are practical, doable, and community-owned. Finally, the WACS became an accurate basis for prioritizing the most appropriate interventions according to the dominant type of waste. These include more biocomposting for fertilizer in urban, community, and backyard gardens for the large volume of biodegradable materials, and more operational MRFs and incentive mechanisms for the handling and management of recyclable materials such as PET bottles, as currently being implemented in Brgy. San Jose in Tagaytay City.

The still immense amount of plastic, as recorded in the WACS, provides enough impetus to review and amend Cavite’s Provincial Ordinance No. 007-212, approved in April 2012, which prohibits and regulates the use of certain plastics. Results of other PEMSEA studies under the ASEAN-Norwegian Project on Reducing Plastic Pollution observed the limited compliance with the Plastics Ordinance in food service industries and in communities, which warrants its review and amendment. The results of the WACS provide basis for the possible banning of dominant types of plastic wastes in the amended Plastic Ordinance, as well as products from plastic residuals that can be supported through the Ordinance (e.g., the use of plastic sachets for ecobags). The WACS also allows barangay and municipal LGUs to update their 10-year Solid Waste Management Plans, and provide more accurate and updated reports to the Department of Interior and Local Government on the LGUs’ environmental compliance in terms of solid waste management. Apart from the significant results, the process of conducting the WACS provided hands-on experience as well as knowledge sharing and transfer, enabling the LGUs, particularly the City and Municipal ENROs, to conduct WACS on their own.

Second, the ESWM Project has catalyzed stronger partnerships and linkages among the Provincial Government through the PGENRO, municipal LGUs, Caritas Diocese of Imus Foundation, and the communities, and has leveraged more technical, human, logistical and other in-kind support from the provincial and municipal LGUs for the implementation of project activities, as well as in complementing the province’s efforts in addressing solid and plastic waste management. The municipal LGUs provided human and logistical support, including the necessary data for the conduct of the all-important WACS, while the PGENRO continues to provide technical, logistical, and in-kind support as well as human resources for the implementation of various activities, including preparations for the establishment of the MRF in Banaybanay, and consultations with the barangay LGUs to enter into a Memorandum of Agreement to sustain the activities beyond the project’s timeframe. Caritas, meanwhile, continues to work not only on waste management, but for more holistic development of resilient and empowered communities.

Waste segregation—shown here in San Jose, Tagaytay—is key to proper solid waste management.

Waste segregation—shown here in San Jose, Tagaytay—is key to proper solid waste management.

Perfect timing

Third, the project itself provides a clear opportunity to amend Provincial Ordinance No. 007-212. It is worth noting that not all provinces in the country have such an ordinance, which puts Cavite on the right track. Fourth, and arguably most important, the ESWM Project has allowed for immense capacity building and community empowerment among the people of Cavite, as well as the organizations that work on the ground there. “It was perfect timing, as we were looking for a partner with a passion to support our program,” says Cayabyab. “Sa Pilipinas, maraming project ang may suporta, pero bagsak na dahil wala na ang funding. But gusto din namin baguhin ang attitude; natutunan ko yan sa integrated coastal management (ICM) ng PEMSEA.” (In the Philippines, many projects have support, but falter because funding runs out. But we also want to change attitudes; that’s something I learned from the ICM of PEMSEA.)

According to Jerel Tabong, Caritas had been invited to collaborate with CCFPI before, but his team had not been ready for the work such a linkage entailed. “Lumakas yung loob namin pagpasok ng PEMSEA. (We were encouraged when PEMSEA came in.) They have been capacitating us as an organization, and one of the things we learned from them is coordination with local government, mostly at the community level—barangay, kapitan (captain) at konsehal (councilor). Now, we’ve leveled up to mayors and local government department heads.

“We benefited a lot from their expertise,” Tabong concludes. “Parang hulog ng langit.” (They’re like a godsend.)

Urban gardens—like this one in San Jose, Tagaytay—make good use of compost made from biodegradable material.

Urban gardens—like this one in San Jose, Tagaytay—make good use of compost made from biodegradable material.

READ THIS AS A PDF